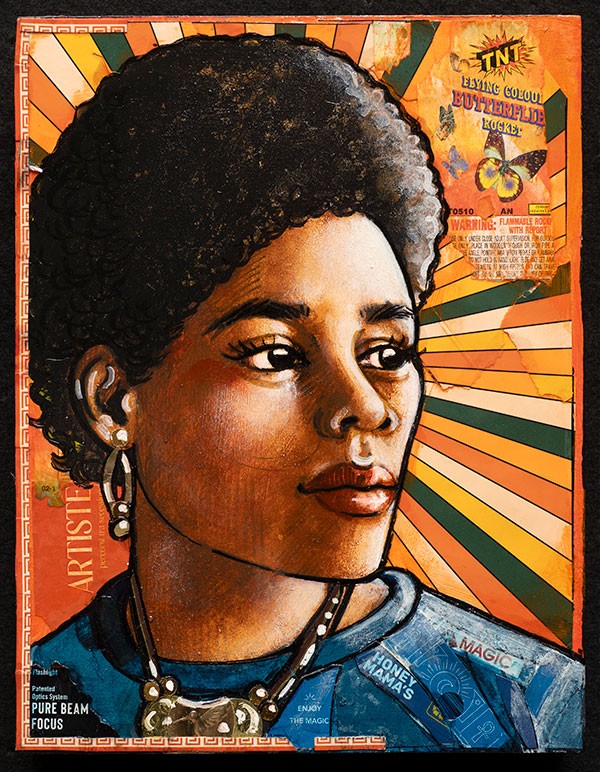

Betye Saar (born 1926—)

In Betye Saar’s work, time is cyclical. History and experiences, emotion and knowledge travel across time and back again, linking the artist and viewers of her work with generations of people who came before them. This is made explicit in her commitment to certain themes, imagery, and objects, and her continual reinvention of them over decades. “I can no longer separate the work by saying this deals with the occult and this deals with shamanism or this deals with so and so…. It’s all together and it’s just my work,” she said in 1989. Saar grew up in Los Angeles and Pasadena, California, and studied design at the University of California, Los Angeles—a career path frequently foisted upon women of color who were interested in the arts, due to the racism and sexism prevalent in universities at the time. Saar eventually studied printmaking, and her earliest works are on paper. Using the soft-ground etching technique, she pressed stamps, stencils, and found materials into her plates to capture their images and textures. Her prints are notably concerned with spirituality, cosmology, and family, as in Anticipation (1961) and Lo, The Mystique City (1965). Saar’s visit to an exhibition of work by Joseph Cornell at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967 profoundly influenced her own artmaking. Cornell’s practice of collecting and arranging found objects into assemblage boxes inspired her to do the same. She began by inserting her own prints and drawings into window frames, as with Black Girl’s Window, an iconic autobiographical work that also signaled a new interest in addressing race and contemporary events in her art. After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., her mystical assemblages became increasingly radical. Saar has since repurposed washboards, jewelry boxes, and racist ephemera as a way of reclaiming images and artistic power. For her best-known work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), Saar arms a Mammy caricature with a rifle and a hand grenade, rendering her as a warrior against not only the physical violence imposed on black Americans, but also the violence of derogatory stereotypes and imagery. The artist has also repeatedly turned to her family and their history as sources for her work. “Keep for Old Memiors” (1976) includes fragments of letters and photographs saved by the artist’s great aunt Hattie, framed by a pair of women’s gloves that suggest, among other things, the tactility of accessing a physical record of one’s life. The intimacy and scale of Saar’s work encourages a personal connection to the artist and her experience. “To me the trick is to seduce the viewer. If you can get the viewer to look at a work of art, then you might be able to give them some sort of message.”

Over the course of her now six-decade career, Saar has continued to make work that honors or critiques the familiar and mines the unknown. “It may not be possible to convey to someone else the mysterious transforming gifts by which dreams, memory, and experience become art. But I like to think that I can try.

Esther Adler, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, and Nectar Knuckles, Curatorial Fellow, 2019

In her own words:

There has been an apparent thread in my art that weaves from early prints of the 1960's through later collages and assemblages and ties into the current installations. That thread is a curiosity about the mystical. I am intrigued with combining the remnant of memories, fragments of relics and ordinary objects, with the components of technology. It's a way of delving into the past and reaching into the future simultaneously. The art itself becomes the bridge. Curiosity about the unknown has no boundaries.

Symbols, images, place and cultures merge.

Time slips away.

The stars, the cards, the mystic vigil

may hold the answers.

By shifting the point of view

an inner spirit is released.

Free to create.

Betye Saar

1998